Before it is too late

In 15 countries — from Israel to Poland, Russia to Argentina, Canada to South Africa — Holocaust survivors sat in front of our cameras to tell their stories. Alone or surrounded by their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren — living proof of their triumph over absolute evil — they spoke of what they saw and lived through, things “that the rest of humanity can barely imagine”. Their testimonies were gathered over three months by AFP teams across the world to mark the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camps by the Red Army on 27 January 1945. Nearly a million Jews were murdered by the Nazis in the vast complex in occupied Poland. Thousands of Roma and Polish resistance members were also killed there.

In Yannick Pasquet’s special report — “Tell what happened to us”: the last death camp survivors — they described what was done to them and to so many millions of others during those dark years. “We are the very last generation” who can personally testify to the horrors, said 86-year-old Evelyn Askolovitch, who was four when she was taken from her home in France to the camps. Some, like 97-year-old Austrian Erich Richard Finsches, feel that the need to keep the memory alive is even more urgent now, because “these are dark times” too.

The idea was to document, film and photograph as many survivors as possible and give them the chance to speak while they still can, said Samantha Dubois, AFP’s Europe Photo Editor, and Deborah Pasmantier, a Deputy Editor-in-Chief in charge of long reads. The youngest of the survivors AFP spoke to were actually born in the camps. They are now in their eighties; the oldest was nearly 110. Some feared the Holocaust would be forgotten — “drowned out” by the weight of history or by the constant stream of social media.

"How did the world allow Auschwitz?" asked 95-year-old Marta Neuwirth from Santiago, Chile. She was 15 when she was sent from Hungary to the largest and most notorious Nazi death camp - Santiago, Chile - © Rodrigo Arangua / AFP

The power of the gaze

AFP journalists on five continents interviewed the survivors between November 2024 and January 2025. Often, they had their portraits taken in front of walls covered with pictures of their descendants — a living, breathing rebuke to the Nazis’ murderous madness that swept away six million Jews. “I wanted them to be photographed straight on, so they were looking directly at us — so we were exchanging not just a look but their personal history — how they had lived their lives as survivors of the unimaginable,” said Dubois, who drew up the guidelines for how they should be shot.

“This is our common history — we are the children of this history — and of what it brings us back to today with the rise of anti-Semitism and populism in Europe and beyond,” she added. “It was also important that they were with their families, because that represents transmission, continuity and the force of life.”

AFP photographers asked the same four questions to each survivor, starting with their deportation; what they have been able to pass on, and what will happen to that legacy once they are gone. Finally, we asked about their hopes and fears for those who come after them.

Almost 100, Julia Wallach cried and went silent as she spoke, her granddaughter Frankie by her side. "It is too difficult to talk about, too hard," she said. The Parisian only survived because she was dragged off a lorry destined for the gas chamber in Birkenau at the last minute. But despite the pain of reliving the horrors, she insisted on giving witness. "As long as I can do it, I will do it" - Paris, France - © Alain Jocard / AFP

Tears and silence

Most of the survivors had been interviewed several times before. Naturally, questions arose about the usefulness of putting them through such trauma again to ask about what is already well documented. But Holocaust historians we consulted stressed the importance of direct testimony at a time when soon no one will remain who was actually there.

“Our approach was to focus on them as individuals, asking open questions to let them choose what they wanted to say — whether for the first or last time,” said Pasmantier. And the survivors went far deeper in their replies than we ever expected.

“At this historic turning point,” when many may soon be gone, “we also wanted to explore how younger generations are taking on this legacy,” said Pasmantier. Especially “at a time when anti-Semitism is rising in ways we haven’t seen since the end of the Second World War — with some even questioning the facts of what happened.”

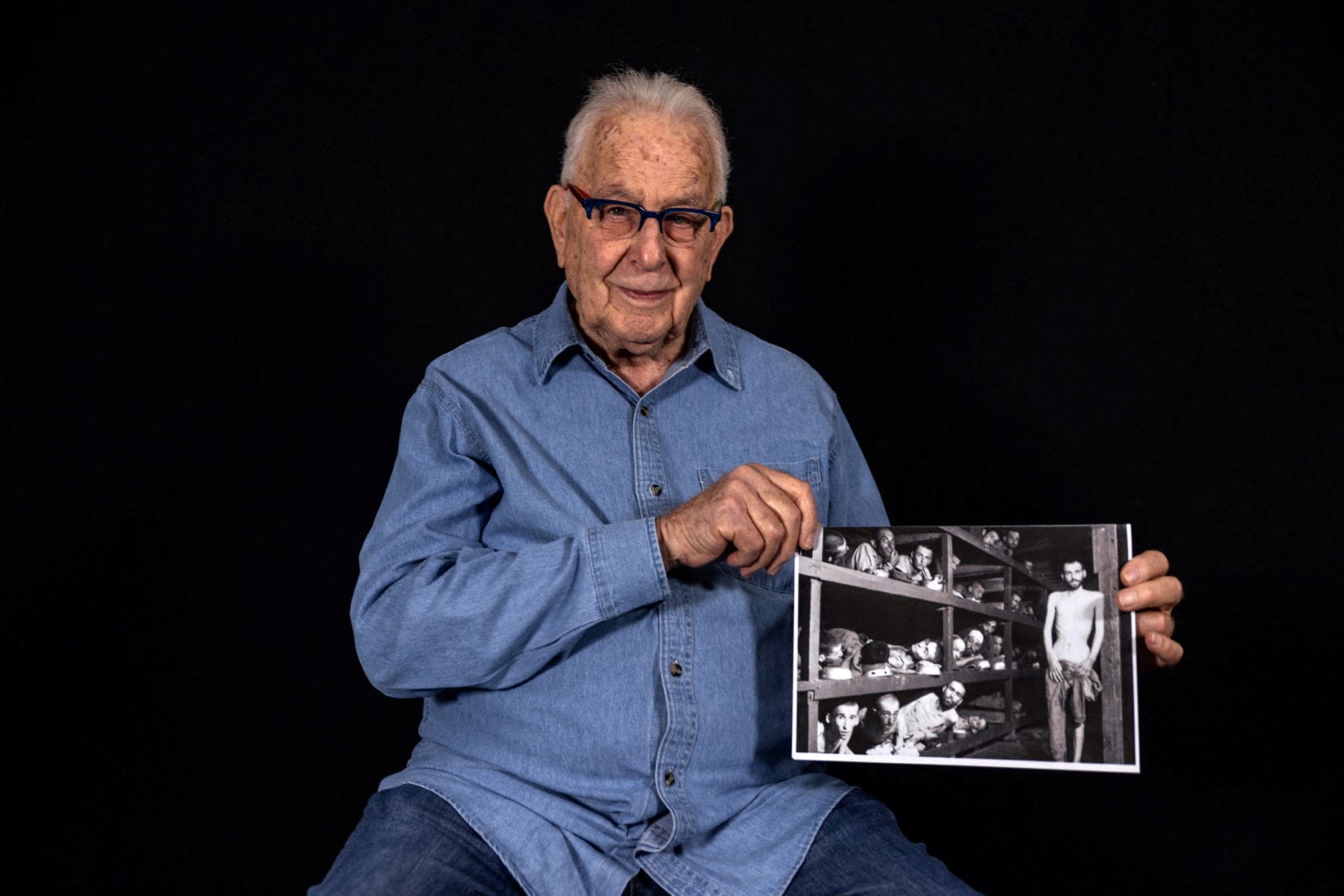

The dehumanisation still marks Polish-born Canadian Nate Leipciger, now 96. In a few "minutes we were transformed from being free people to being incarcerated in a concentration camp with numbers on our arms. "They removed our clothing, our hair, and everything that was personal, so you became just an object, and you lost all your ability to function as a human being" - Delray Beach, USA - © Marco Bello / AFP

“The hours of recordings were difficult to listen to,” Pasmantier admitted. “The tears, the silences, the depth of the pain. But there were also happy childhood memories that surfaced unexpectedly, as well as the love and affection between them and their grandchildren.” There were touching exchanges too, she said — as when South African survivor Ella Blumenthal told AFP’s Gianluigi Guercia: “You really look like my cousin from Paris.” Some found it very hard to speak, but insisted on doing so — “because we must”. Others, to Pasmantier’s surprise, were upbeat, even joyful, speaking of “the miracle of life, despite everything”.

Seeing her Roma culture and language fade adds to the suffering of Vienna-born Rosa Schneeberger. "The Sinti are disappearing," said the 88-year-old who was sent to the Lackenbach "gypsy" camp in Austria when she was five. "Most died during the war" and there are not enough survivors to keep the community going, she said - Villach, Austria - © Joe Klamar / AFP

'Too hard'

Of the survivors contacted through the Auschwitz Museum in Poland, “not all of them agreed” to speak, said AFP photographer Wojtek Radwanski. “For some it was too difficult, for some too exhausting.” In Argentina too, some survivors were “very old, had difficulty speaking, or suffered from memory loss,” said photographer Juan Mabromata in Buenos Aires. He admitted feeling “uncomfortable” about asking to photograph the camp tattoos on their arms. But after meeting them, his only regret was: “I wish I had done this story earlier, when they were younger.” Polish-born Lola Mandelkier Sztrum, now 101 — who survived both Majdanek and Auschwitz — had such a “peaceful face”, he said. “She fell asleep while we were there taking photos and speaking with her daughter.”

Argentinian survivor Lola Mandelkier Sztrum - Buenos Aires, Argentina - © Juan Mabromata / AFP

There was also a “really intense moment for everyone” when 88-year-old Petr Polacek, born in Czechoslovakia, told Mabromata about his time in the Theresienstadt camp. “We realised his daughter was upset — she was hearing part of his story for the very first time,” and asked why he had never told her before.

Petr Polacek and his daughter Karina - Buenos Aires, Argentina - © Juan Mabromata / AFP

'The art of surviving'

“Every now and then”, said AFP’s South Africa-based photographer Gianluigi Guercia, he listens again to the recording of his conversation in Cape Town with Ella Blumenthal, who lost her entire family in the Holocaust. “She had the greatest impact on me,” he said. “I was deeply moved by how someone who went through such events — surviving Auschwitz and Majdanek — could still be so full of life, even at 103.

“She kept referring to ‘the art of surviving’ — and indeed, she was an artist at it. One of the stories she shared was particularly moving: she and her niece were inside the gas chamber, waiting to be killed. They had already said goodbye to one another, but someone realised they were in the wrong group. They were called out, and their lives were spared. Such a story puts everything into perspective,” Guercia said.

South African Ella Blumenthal and her daughter Evelyn Kaplan - Cape Town, South Africa - © Gianluigi Guercia / AFP

He also mentioned the image of 100-year-old Henia Bryer, which, to him, captured everything the Nazis had inflicted. “It shows the identification number tattooed on her arm — a true symbol of dehumanisation. It is both a visual and physical testimony to the evil perpetrated, and to the systematic method used to exterminate an entire people.”

Polish-born Henia Bryer. - Cape Town, South Africa - © Gianluigi Guercia / AFP

“We’ve done many stories about the Holocaust, the Second World War, and the death camps — it’s part of the job in Poland, unfortunately,” said Warsaw-based photographer Radwanski. “I’ve learned something from every one of them. But the most striking for me was the session with Marek Dunin-Wąsowicz and his grandson. The bond between them — and their shared sense of humour — was remarkable, even though Marek is now 99.”

Pole Marek Dunin-Wasowicz and his grandson Roch - Warsaw, Poland - © Wojtek Radwanski / AFP

Guarding the memory

Athens Bureau Chief Yannick Pasquet — who, in her previous post in Berlin, covered the last Nazi trial held there — had the task of weaving these testimonies together. In a poignant twist, there were no Greek Jewish survivors left from Thessaloniki able to speak to her — even though they once formed the majority of the city’s population. “The idea was to make each testimony personal, so that we could relate to something universal about the human condition,” she said.

One phrase from Marta Neuwirth — who was 15 when she saw women calmly led into the gas chambers — immediately stood out for Pasquet: “How did the world allow Auschwitz?” “She gave voice to the fundamental question that has haunted the world since 1945,” Pasquet said.

The story of Polish-born Canadian Pinchas Gutter also left a mark on her. The 92-year-old spoke about not being able to remember his twin sister Sabrina’s face. She was murdered in Majdanek when they were 11. “All he remembers is her beautiful blonde braid. That said everything. Everyone in the world can relate to a testimony like that.”

“Reading all of these testimonies took time and was emotionally tough,” Pasquet said. “But at the same time — despite all they endured, and despite the world’s current state — every one of these survivors carried a message of hope.”

Naftali Furst, a 92-year-old Israeli Auschwitz survivor born in Bratislava, has been going to Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic for years to tell his story "so the younger generations never forget what happened" - Haïfa, Israël - © Menahem Kahana / AFP

A dozen video portraits of survivors were also filmed, using the same approach and the same four questions as the photo interviews. “Their testimonies were so powerful that, for our long-format videos, we decided to let their words stand on their own — with no narration, banners, or captions,” said Gabrielle Chatelain, Deputy Editor-in-Chief for Video.

The 12-minute film ended “naturally” with Julia Wallach, she said. Because Wallach found it so hard to speak about what had happened to her, the raw footage of the French Auschwitz survivor initially seemed difficult to use. But it was incredibly moving at the same time: her granddaughter Frankie gently guiding her, hugging her, encouraging her to go on. In the end, it was her granddaughter who told the story — history passed on before our eyes.

DISCOVER MORE ON THE TOPIC:

Explore our coverage. Get an AFP News free trial.