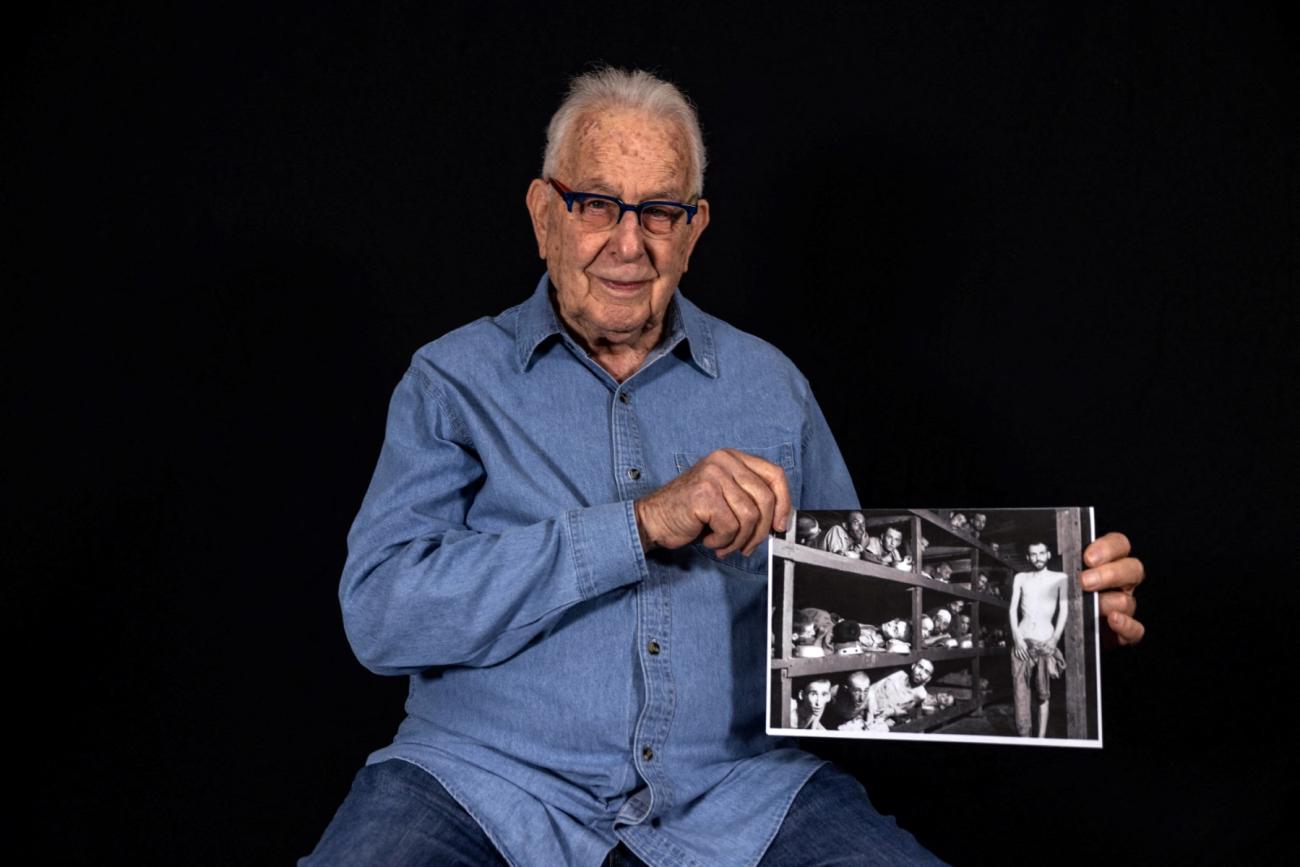

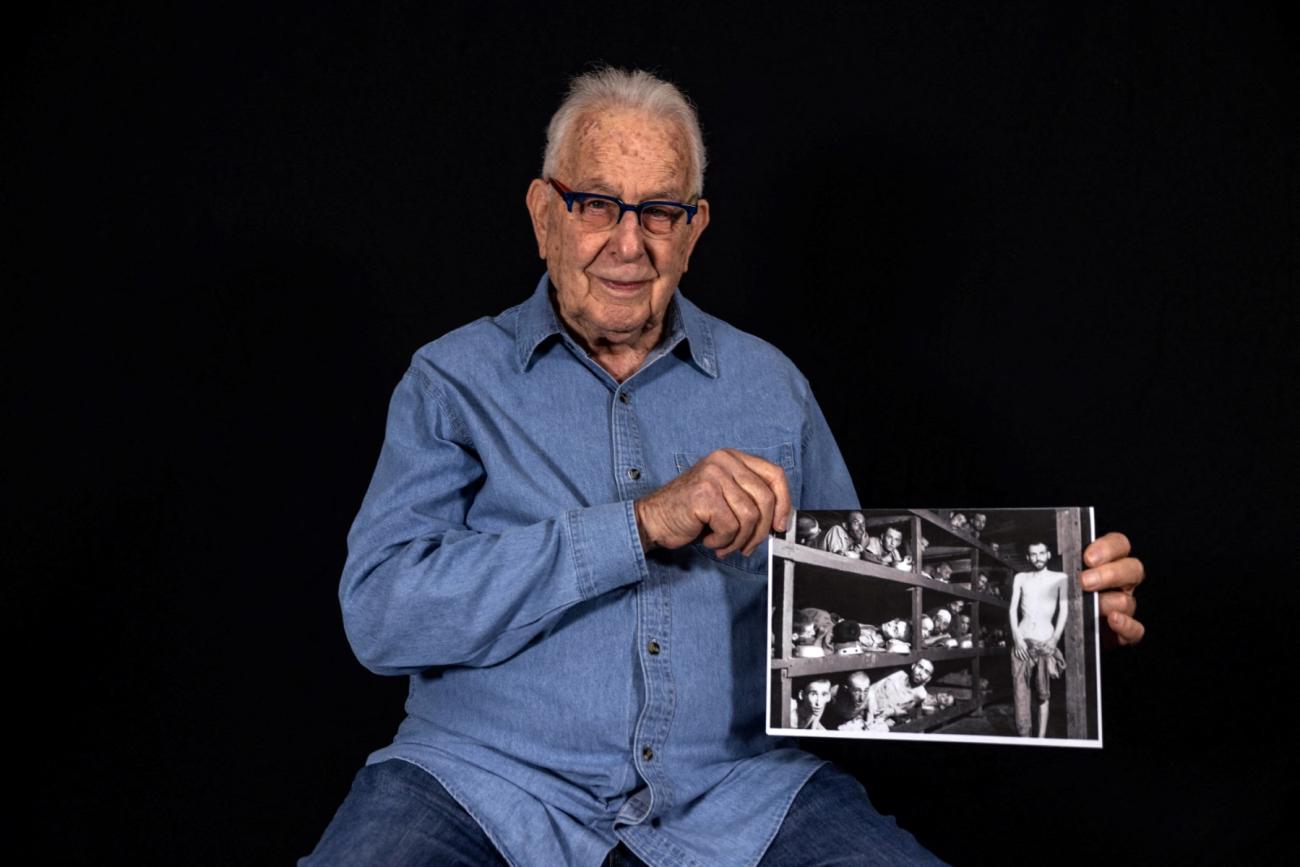

Before it is too late

The power of the gaze

Tears and silence

'Too hard'

'The art of surviving'

Guarding the memory

Explore our coverage. Get an AFP News free trial.

Washington (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 21:16:40 | US says supports gas deals with Kurdistan region after Iraq lawsuit

Jerusalem (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 20:42:33 | Israel PM acknowledges 'loss of control momentarily' at Gaza aid centre

Washington (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 20:34:16 | US calls UN criticism of Gaza aid effort 'height of hypocrisy'

United Nations (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 19:23:11 | UN says images of Gaza aid rush 'heartbreaking'

Paris (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 19:12:53 | Macron welcomes France's right to assisted dying bill vote

Mexico City (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 19:01:31 | 17 bodies found in abandoned house in Mexico: prosecutors

Paris (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 18:49:43 | France's lower house backs right to assisted dying bill

Istanbul (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 18:18:38 | Turkey's top diplomat to travel to Kyiv this week: official

Washington (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 17:53:34 | Trump says Putin 'playing with fire'

Rafah (AFP) | 27/05/2025 - 17:50:28 | Thousands rush into new aid distribution centre in south Gaza: AFP journalist